I am never sure if we altogether understand self-drilling screws, the need for pilot holes, and just what’s happening at the tip of the screw with its ultra-pointed, missile-shaped point. In industry, carpentry-level assembly and such, they are indispensable and an odd split in a deck board will ultimately add to the dozen or so other shrinkage and expansion cracks anyway, regardless of the screws. But it is in benchwork and finer work where the ultimate cost can ruin our work. Oh, and I know some carpenters who go to the same extremes I do to prevent or lower the risk of a board splitting because of a wrongly driven screw too. This weekend I was driving screws in the stops of my greenhouse glazing panels and a few other places too. All of my holes were predrilled. I do this on almost all of my work. I have experimented to ascertain exactly what happens within the wood. Predrilling is an imperative step for me.

Not too many people in woodworking use slot- or flat-head screws these days. It is a strange thing but when the screws are visible, slot-heads remain unsurpassed for looks. I use mostly brass screws on all brass fittings, but when a wood screw is necessary say for dismantling in a piece of work, I will look to a slot-headed version. An instance in mind also is the black-japanned round or dome-headed screws used on gate and door furniture outdoors. Somehow, the cross-headed screws never seem quite right. Ultimately, my opinion will die with me, I know that, but until then I will always have the beautiful advantage of lining up that slot with the perpendicular or horizontal axis of whatever is being fixed.

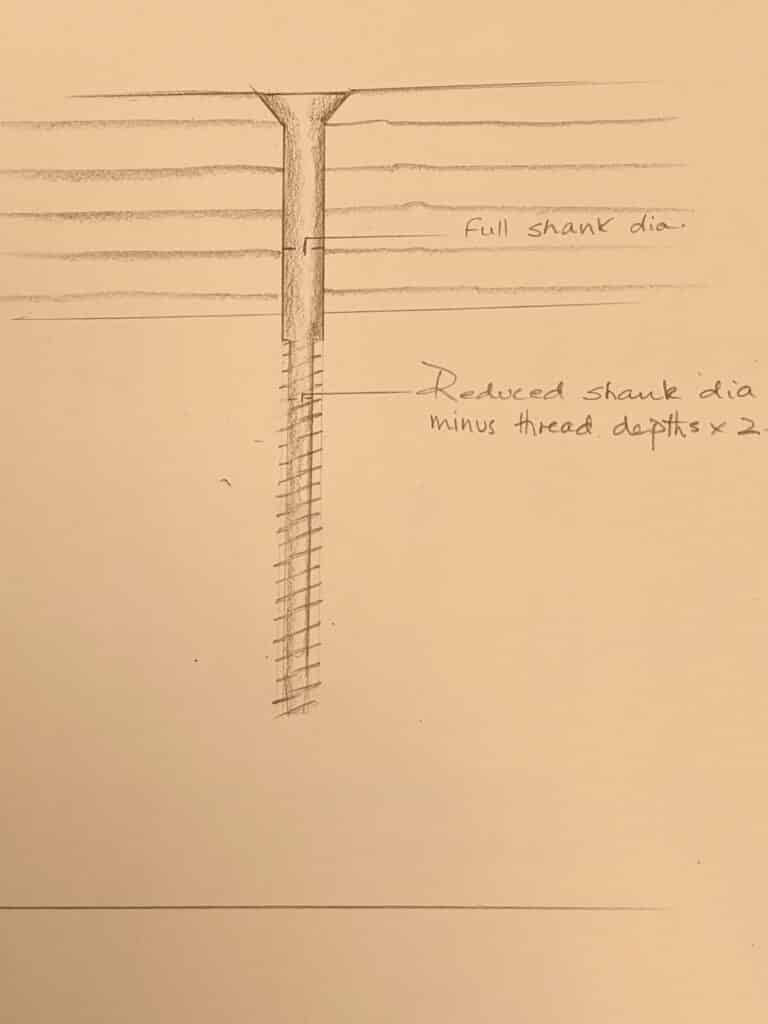

A point without pun worth making is the reality that it is not just the point part of the screw that eases access of the screw into the wood. This is only really a start point that eases the screw in, yes, but then the thread takes over with heavy force from the drill to pull the screw and the shank or main body of the screw into the wood. The sharpened and refined point with its reaming capacity does not drill away the wood beyond the first percentage of the length. The screw itself cannot remove any wood because the shank of the screw does not have the flutes that twist drill bits do, so at best what the self-drilling screw does is fracture the fibres. The wood remains within the threads of the screw and because of this, the wood is very likely to split at some point. This is especially problematic with resilient hard and dense-grained hardwoods. The denser the wood, hardwood, or softwood, the more likely the split. I think that it is important to note here that it will always be best to drill a stepped hole of lesser diameter to ease the circumferential pressure caused by the screw’s reduced shank even though the screw shank is smaller in diameter.

Pre-drilling is not always pilot hole drilling and we do tend to call such holes pilot holes. Predrilling is not to pilot and guide the drill bit into the cut even though it does do that too. A pilot hole encourages the screw to follow a particular path and especially is this so when planning to screw into narrow edges and such. This can be important in some or many situations. The screw can and often will take the path of least resistance. It’s not at all unusual for a screw to follow a radius of a growth ring is a good example. This is especially so where the growth ring comprises extra hard and extra soft aspects to each growth ring as in almost all softwoods. Hardwood growth rings tend to be equally consistent throughout the wood. We use predrilled holes to accept both the whole shank of the screw and also the reduced diameter within the threaded area so that the threads bite into the wall of the hole. Often, woodworkers drill a smaller hole so that the screw is simply easier to drive. The problem occurs nearer to the head where the diameter has no thread and the driven screw can and will cause the wood to split.

Predrilling, its purpose, is to accommodate the metal either entirely, as in the shank of the screw, or partially as in the unmilled area beneath or below the thread start-line. Although we rarely if ever measure the inner, reduced diameter we do aim for closeness to size. All we really need is for there to be sufficient bite of the threads into the wall of the hole. Usually, we become adept at gauging hole sizes by eye and based on previous experience. Of course, there is nothing wrong with measuring the sizes using a gauge too.

In general, we use screws for two reasons. one, we use screws to unit two pieces of wood and, two, we use screws to attach fittings such as hinges and handles to the wood. Either way, using stepped drilling ensures that we minimise or eliminate splits in our delivery of screws. In my work, self-drilling screws don’t quite cut it even though I like them.

Before anyone writes in to comment on this screw-type or that screw-type being the bestest and mostest, that is not what this article is about. It is purely to explain why, in furniture making and other aspects or areas of woodworking, it will always be best to pre-drill almost all of your screw holes and where necessary to do them in two steps as step stages, to use countersinks for seating the screw head properly and then to rely on patience to make sure you work with care.

Although wood screws do look tapered along the length, they are actually parallel along the whole length from the underside of the head to the near-pointed tip of the screw. In my world as an apprentice, where no battery-driven drill-drivers existed, we predrilled every hole we made to receive a screw using either a drill bit or square awl. Not much was explained but I learned why by investigating all things in my even as I still do today. To illustrate my point, the picture below shows the difference between driving only the screw to drill straight off and then a hole bored with a twist drill bit. You can see the screw-drilled hole to the left removed almost no waste and the waste that was parted off jammed into the recessed point of the screw tip compressed the fibres as it baked with the heat generated by the screw interaction with the wood–this waste came out with the screw when the screw was withdrawn.

There is no wood fibre on the outside of the hole as nothing of real consequence was removed. This shows that the sole purpose for the drill point is to merely start the screw and sever the fibres as progress is made driving the screw. The second hole shows that all of the wood fibres are removed equal to the diameter of the bit used and this alone minimises any possibility of splitting because, of course, force is drastically minimised.